Hello and welcome!

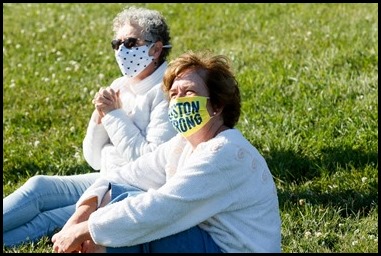

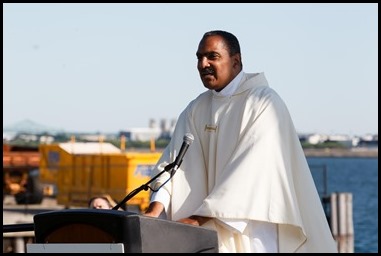

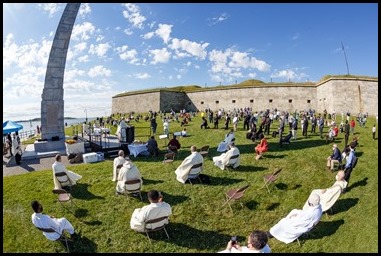

Last Saturday, I went to Castle Island in South Boston to celebrate a special Mass for racial justice and healing.

I was very gratified to be a part of that celebration at the very place that the parishioners from St. Brigid’s and Gate of Heaven usually have their sunrise service on Easter. I thought it was very significant for us to have this Mass there, particularly considering there has been a difficult history around the issue in South Boston.

I was most edified by the presence of so many black ministers at the Mass, including Rev. Gene Rivers, Rev. Ray Hammond and his wife, Gloria and, of course, Bishop William Dickerson, who gave a very beautiful talk before the Mass.

After the Mass, one of the black priests who was with us told me that when he came to Boston in the 80s, his friends told him not to go to Southie because it would be too dangerous for him. So, having a Mass there around the theme of racial justice and the Church’s social teaching was very poignant.

I’d like to share my homily from the Mass with you here:

It is a privilege for me today to join with you in prayer, we pray first of all for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and all of those known and countless unknown who have been victims of racial violence in our land. Today, we pray for healing, reconciliation that will come about by deeper commitment to racial justice and equality. Thank you for your presence here today.

In the 20 years I lived in Washington, I came to look forward to the annual event sponsored by the Washington Post, the naming of the person who would receive the most parking tickets during the course of the year. Sometimes I thought I was a candidate. Actually, there was not much suspense; it was always the Russian ambassador. Diplomats do not need to pay fines, so I am sure that was a factor. A bigger factor was that we were in the Cold War, and the Russians were seen as the evil empire and deserving of as many parking tickets as possible.

At the time of Jesus, there was a bitter cold war between the Samaritans and Jesus’ own people, the Jews. I have always considered the parable of the Good Samaritan my favorite. I like to imagine the impact that this story made on Jesus’ audience when the world was hearing this parable for the first time. The hero of the story is a member of a persecuted and despised minority group. In those days, the words “good” and “Samaritan” did not appear in the same sentence.

In the parable, Jesus describes a man beaten by muggers and left half dead by the side of the road. Some very respectable people, even clergy, happened by; but looked away, and passed by on the opposite side. The Samaritan came by and saw the man in pain. He did not turn away; he did not pass to the other side of the street. He was moved with compassion. I wonder if it did not occur to the Samaritan that by drawing near, he was taking a risk. People could look at him and say with suspicion: “There is a Samaritan, he must’ve beaten and robbed that nice man bleeding by the side of the road,” I am sure that the Samaritan knew what discrimination was. He would have suffered the sting of humiliation, suspicion, and rejection whenever he ventured outside of his own community. Jesus’ original audience would have felt uncomfortable with this parable. They would’ve been embarrassed, perhaps indignant. How could a Samaritan be the hero? Jesus is reminding us that so often we judge people by their appearance, by their circumstances. We focus on what differentiates us rather than what we have in common. In another place in the Gospels, Jesus tells his disciples to learn to turn the other cheek, to give your cloak as well to the one who asks for your tunic, to go two miles for the person who bids you go one mile. The Good Samaritan was certainly a man who went the extra mile. He does not call 911 and drive away. He draws near; he gets mud and blood on his clothes. He puts the injured man on his mount and takes him to a safe place. Then he pays for the man’s care. The Samaritan commits to following up by coming back and taking care of any other expenses.

Like the Samaritan, we have to understand that there is no quick fix for the harm that has been done. We need to return again and again to face the situation, to nurture change and recovery. It will not happen without the sustained effort and focus of all. It is not enough to draw near once for a demonstration or a prayer service and then turn our backs and cross over to the other side of the street. The symbolic gesture or compassionate word is not enough. We need concrete reform, transparency, and determination to do what needs to be done to pay the price to work together and make it happen. This may be our last chance. It is impossible to exaggerate the sense of urgency we must have as Americans. Christ’s most beautiful parable comes to us because of two questions from a lawyer, of all people — questions that were posed with cunning and malice. Yet they are very important questions that we must ask ourselves. “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” The answer is, love God and love your neighbor, then you will live. The second question was a face-saving one, “Who is my neighbor?” This is the question that Americans must ask ourselves today. So many studies have shown how we are isolated by ZIP codes, by racial, ethnic, and religious divides. We live in bubbles that allow us to turn away from each other and cross to the other side of the street. Jesus is telling us that our neighbor is not just the person who looks like me, talks like me, thinks like me, or roots for the same baseball team.

The neighbor is the Samaritan. That is the punch line; that is the surprise. The Samaritan is the one who draws near, who crosses the barrier, who cares because he knows every single person matters.

George Floyd was left by the side of the road, crushed on the ground. We cannot turn our backs and walk away without being guilty bystanders. George Floyd was not just murdered by a rogue police officer. He was murdered by slavery and its legacy of racism. He was murdered by those who turn their backs on racial violence, by those people who teach their children to be prejudiced, by those who know that it is evil but are too cowardly to speak up, by those who profit by exploiting others, by police unions who failed to see that the best way to protect good police officers is to get rid of the bad ones. We have learned this in the Church. This cannot become a national contest between forces of political correctness and the forces of law and order. Then everybody loses. This cannot be about partisan politics. But if we use this moment to play politics, it will be another false start doomed to failure. Blacks and whites together; Republicans, Democrats, Independents together; people from the blue coasts or the red flyover states; Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, Jews, Muslims, agnostics, and unbelievers.

At a time like this, it is easy to forget how well-served we have been by our police force and first responders who at times like the marathon bombing or during the pandemic have risked their lives to protect others. We are blessed by the leadership of Mayor Walsh and Commissioner Gross, who truly care about the community. Wherever there have been problems, Mayor Walsh and the Commissioner, along with local clergy, have worked hand-in-hand. We all need to work together.

The death of George Floyd fills us all with shame and indignation. It has been half a century since the murder of Martin Luther King and these horrors should be behind us, but sadly they are part of our present. It has been said that the original sin of America is racism. This is an American problem. It has been 401 years since the first slave ship arrived at Point Comfort and 155 years since the last enslaved Americans were freed in Galveston. This is in our history; it is in our DNA, and together we need to find a vaccine, or it will destroy our country.

We have to become Samaritans. The Samaritan did not turn his back and walk away. He could see, not just the differences with the man by the side of the road, he could see his humanity, his connectedness. He wanted to be his neighbor. Racial tolerance is not enough. We need reconciliation, solidarity, and a commitment to anti-racism. We need to be a real community. We need to take care of and care for each other.

They tell the story of Cardinal Spellman, who was the Archbishop of New York, who one day received a call on the intercom. It was the new receptionist calling from the lobby of the chancery. She whispered, “Your Eminence, there’s a man in the lobby who says he is Jesus Christ, what should I do?” The cardinal said, “Look busy!” The droll remark of the cardinal was true — that homeless, off-his-meds, schizophrenic man is Christ in a distressing disguise, as Mother Teresa used to say.

The person who is hungry, sick, imprisoned, or a stranger is our neighbor, our brother or sister, and, for the believer, is Christ. We must look busy because God is watching us. He sees not only what we do but what is in our hearts. Indeed, the whole world is watching us. It’s amazing to see the demonstrations inspired by the murder of George Floyd in cities and countries throughout the world: millions of gathered throughout the United States, London, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Holland, Australia, Vienna, Norway, Rome, Liberia, Canada, Greece, Berlin, Paris, Korea, Barcelona, Madrid, Rio de Janeiro and Hungary. The world is watching. The world wants more from America; the world wants a better America. If America is to champion democracy, human rights, equality, freedom in the world, we need to clean up our own act. The death of George Floyd has shaken many of us from our complacency and our complicity. We need to show the world and each other that we are truly committed to justice and that we are capable of transformation.

The world needs a better America where racism and inequality will not be tolerated. The pandemic has unmasked the disparity of healthcare along racial lines in our country. We are painfully aware of the high incarceration rates and the lower life expectancy of black Americans. The economic inequities and lack of opportunities are direct results of the vile institution of slavery and its poisonous legacy of racism.

We are in a historic moment that causes us to stand together as Americans, to be neighbors to each other, to overcome racial prejudice and institutional racism.

Racial tolerance is not enough; the antidote to racism is not just tolerating each other. The cure is solidarity and community. We have to want to be neighbors, to be brothers and sisters, even when we are not twins.

The Eucharist we celebrate today is our daily reminder of how God’s gift and our work come together. We bring our gifts to the altar; God transforms them, and we receive them back and are transformed ourselves, more prepared for our mission to bring compassion, justice, and healing into our broken world. As we contemplate the figure of the Samaritan whose courage and sacrifice made him neighbor to the man half-dead, the man who could not breathe, lying on the ground, let us heed Jesus command from today’s Gospel: “Go and do likewise!”

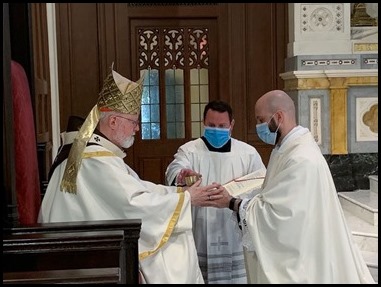

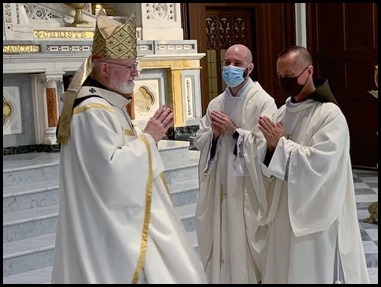

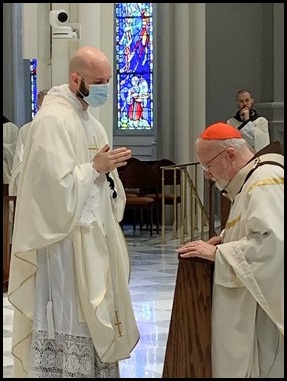

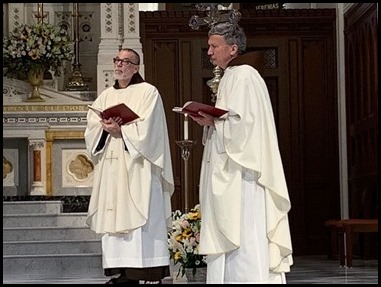

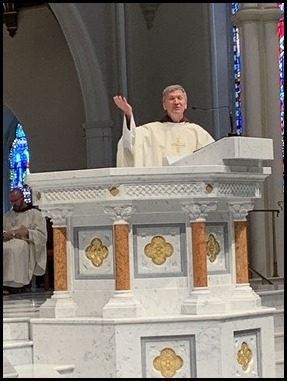

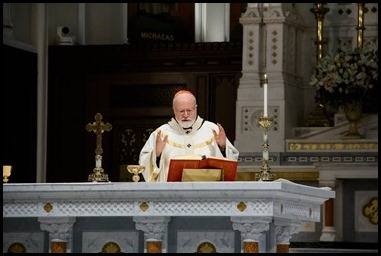

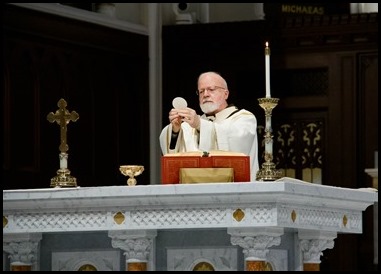

Later that day, I was very happy to celebrate the ordination of two Capuchin brothers at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross — Brother Diogo Escudero to the priesthood and Brother Keon Tu to the transitional diaconate.

With us were our provincial, Father Tom Betz, and the guardian of Capuchin College, Father Paul Dressler.

With us were our provincial, Father Tom Betz, and the guardian of Capuchin College, Father Paul Dressler.

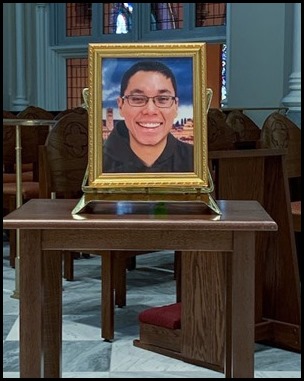

We also remembered their classmate, Brother Saúl Soriano, who would have been ordained with them but died suddenly a year ago.

We also remembered their classmate, Brother Saúl Soriano, who would have been ordained with them but died suddenly a year ago. It was a joy to be able to celebrate the ordination here in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. We are so grateful to CatholicTV for live-streaming the Mass so that our Capuchin Friars and their families that are in different corners of the world — Father Diogo is from Brazil and Deacon Keon is from China — were able to watch it.

It was a joy to be able to celebrate the ordination here in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross. We are so grateful to CatholicTV for live-streaming the Mass so that our Capuchin Friars and their families that are in different corners of the world — Father Diogo is from Brazil and Deacon Keon is from China — were able to watch it.

Sunday was, of course, the Feast of Corpus Christi and marked the start of our Year of the Eucharist in the Archdiocese of Boston. As many of you know, we had originally planned to begin the Eucharistic Year on Holy Thursday. However, because of the restrictions on public Masses, we decided to postpone it until Corpus Christi.

Although we are unable to hold large gatherings at the present time, we are hoping that there will be a number of activities in the parishes to mark the Year of the Eucharist. That is why, last week, we commissioned over 450 Eucharistic missionaries from the various parishes to help promote different ideas for local observances.

Although we are unable to hold large gatherings at the present time, we are hoping that there will be a number of activities in the parishes to mark the Year of the Eucharist. That is why, last week, we commissioned over 450 Eucharistic missionaries from the various parishes to help promote different ideas for local observances. I think that after the long period of being unable to receive the Eucharist, people are anxious to return to Mass and receive Holy Communion. Hopefully, this will be an opportunity for us to reflect on this great gift and to live the spirituality of the Eucharist, which is one of unity, service and love. That sign of unity, service and love is what the world needs so desperately today.

I think that after the long period of being unable to receive the Eucharist, people are anxious to return to Mass and receive Holy Communion. Hopefully, this will be an opportunity for us to reflect on this great gift and to live the spirituality of the Eucharist, which is one of unity, service and love. That sign of unity, service and love is what the world needs so desperately today.

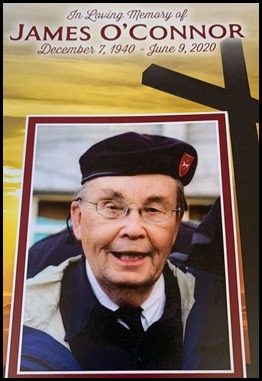

On Monday, I attended the wake of Jim O’Connor, who was very much involved in the Order of Malta, his parish and the life of the archdiocese. He lived out the spirituality of the Order of Malta, particularly with the care of the sick and the poor. He would go every year on the pilgrimage to Lourdes and was always very much involved in different works of mercy. We will always be grateful for the luncheons that he and Jack Joyce would organize each year for our senior priests at the Boston College Club.  I was happy to be able to lead the services at the funeral home with his family. He will be sorely missed in the archdiocese.

I was happy to be able to lead the services at the funeral home with his family. He will be sorely missed in the archdiocese.

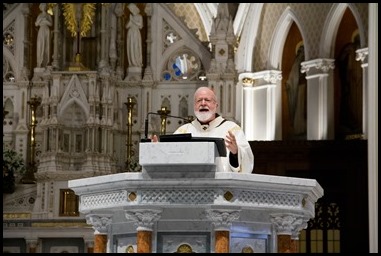

Thursday, we were happy to host a baccalaureate Mass for Boston College High School at the cathedral.

Of course, they couldn’t gather with the students as they usually would, but thanks to CatholicTV, they were able to live-stream the celebration to the school community.

Until next week,

Cardinal Seán