Hello and welcome!

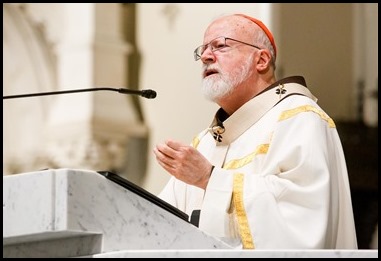

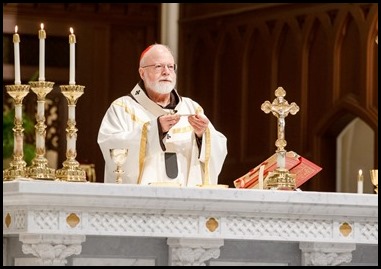

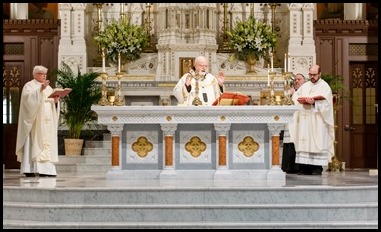

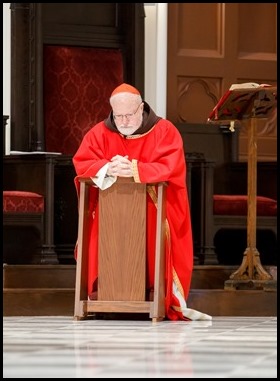

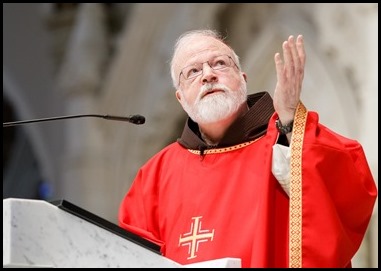

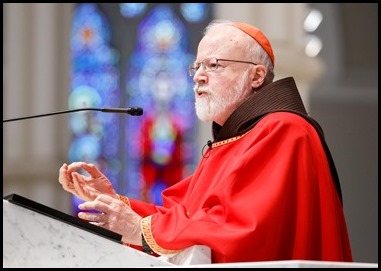

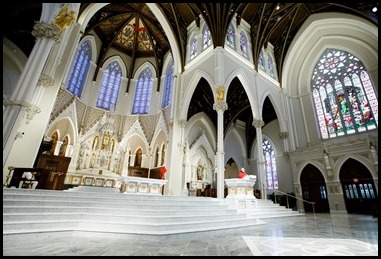

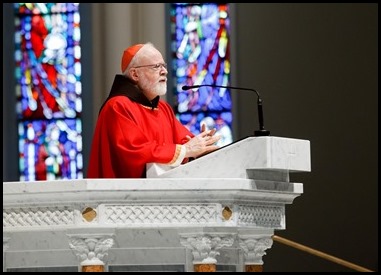

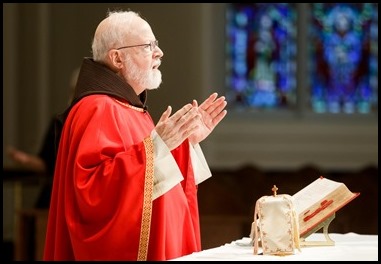

Palm Sunday was, of course, the beginning of Holy Week, and this year was certainly a unique event, celebrated as it was in an empty Cathedral the Holy Cross. It was particularly striking because Palm Sunday is a day when there are usually very large crowds with us for Mass.

First, I celebrated Mass in English, and then I celebrated Mass in Spanish with Father Pablo Gomis in the Cathedral’s Blessed Sacrament Chapel. Of course, we were very conscious of the fact that so many people would have liked to have been present that day, but we were offering the Masses especially for them, their families and particularly for the many people who have fallen ill from the coronavirus. As I mentioned last week, among those afflicted with the virus are six priests of the archdiocese, and I would ask everyone to keep them in their prayers.

I would like to share my Palm Sunday homily with you, and for those who speak Spanish, I am including the video of my Mass in Spanish.

I am sure that we all have great memories of many celebrations of Palm Sunday in the past. The beginning of Holy Week with a procession of the palms is usually a celebration marked by enthusiasm and excitement. But as I look back over my long life, there are certainly three Palm Sundays that stand out. The first one was April 7, 1968. That was three days after the assassination of Martin Luther King. The assassination occasioned terrible rioting in Washington, D.C., with over 700 fires in the city. They brought fire trucks from Richmond and Philadelphia to help. For several days the White House was surrounded by tanks, and there were soldiers with bayonets on every street corner in Washington. There was a curfew, a lockdown. I was living in the basement of Sacred Heart Church on 16th Street with 300 men, women and children, mostly immigrants and some old people whose buildings had been burnt down. Palm Sunday was the first day we emerged from the lockdown, and we processed through the neighborhood with the palms, surrounded by the destruction left behind by the rioting.

Palm Sunday 1980 was also a very dramatic moment in my life. That was the day of Archbishop Romero’s funeral after his assassination while celebrating Mass in a Catholic hospital in San Salvador. There were 100,000 people in the plaza in front of the Metropolitan Cathedral of San Salvador for his funeral. Cardinal Corripio’s homily was interrupted by gunshots and then explosions in the plaza. Six thousand people rushed into the cathedral. Many were injured, some died in the stampede that followed as 100,000 people fled from the square. Afterwards, the empty plaza was strewn with shoes and sandals that people lost as they stepped on each other’s feet in an attempt to get to safety. Besides the hundreds of shoes, there were palm branches everywhere on the ground.

2020 is another very dramatic Palm Sunday, not just in one city or one country but throughout the world. Usually, Ash Wednesday and Palm Sunday are two of the days when most Catholics come to church, and the crowds are overwhelming. Today the churches are empty because of the threat of a virus.

Today’s Gospel, in the passion of St. Matthew, presents the somber images of the darkness, the earthquake, the torn veil in the temple, but to all of these, we can now add the coronavirus, that in a few short weeks has carried off thousands of people and upended the social and economic life of the world.

In some ways, these three dramatic Palm Sundays are probably more like the original Palm Sunday than the festive and celebratory atmosphere that we usually associate with Palm Sunday. Indeed, the Gospel portrays the triumphant entrance of Jesus into Jerusalem as a surprising interlude to the terrible events that are about to take place.

I have always been struck by the fact that the very large crowd of people who spread their cloaks on the road and cut branches from trees to strew them on the path, and who cried out: “Hosanna to the son of David, Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord, Hosanna in the highest,” were the very people who, five days later, are voting for Barabbas over Jesus and who are shouting: “Let him be crucified… His blood to be upon us and upon our children.”

In the Passion account presented by St. Matthew, we glimpse an array of people whose attitudes and behavior have been replicated in every generation by men and women whose reactions to Jesus Christ are similar. Some, like the Pharisees, hate Jesus and want to destroy him. Others, like Peter, are afraid to be identified with him because they know that friendship with Jesus can be dangerous, and therefore pretend to not even know him. Some, like Judas, choose money over Christ. Others rise to the occasion, overcoming fear of criticism or rejection like Joseph of Arimathea, who had the courage to ask for the body of Jesus so he could bury it with dignity. Others, like Pilate’s wife, try to defend Jesus, but their words seem to fall on deaf ears. Still others, like Pontius Pilate, want to do the right thing but don’t have the courage of their convictions and end up washing their hands of responsibility if not from guilt.

Peter and Judas were apostles, and yet in the moment of crisis, they abandoned their vocation. Both of them experience the darkness, the shame and the emptiness that their sin brought to them. When Peter hears the rooster’s crow, he repents and weeps bitterly. Judas, on the other hand, is unable to seek forgiveness or to forgive himself, and so he despairs.

It’s interesting for us to reflect on where we fit into this Gospel. How would we have reacted if we had been in Jerusalem 2000 years ago when Jesus entered the city triumphantly and then was arrested and crucified? The Gospel documents the different reactions of the people who witnessed these events. We can only imagine how many more were oblivious and indifferent to everything that was taking place — just as in today’s world there are people who are opposed to Jesus and his message, others embrace it, others are embarrassed by it, and others are completely indifferent.

Today, I want to hold up for our reflection and consideration two of the characters that appear in the Passion — Simon of Cyrene and Joseph of Arimathea. Granted, they only have walk-on parts, but reflecting on their experience can help us to understand the Passion of Christ and its implications for our life of discipleship.

When I was bishop in the West Indies, I sent one of our seminarians to the seminary in Florida to do his studies. I called him the day he arrived to see how he was making out. The seminarian who had quite a sense of humor said: “Bishop, it’s great. Everybody knows my name.” I immediately understood what he was telling me. He was the only black seminarian there. Well, Simon of Cyrene was African. I am sure that he must have felt put upon and even the victim of discrimination when the Roman soldiers, out of the throngs of people on the streets of Jerusalem, picked him to help carry the tools of execution of a convicted criminal. I’m sure that he felt humiliated, angry and deeply embarrassed.

We don’t know much about Simon of Cyrene. Three of the Gospels talk about him being forced to help Jesus carry the cross. Mark’s Gospel mentions that Simon was the father of Alexander and Rufus. The name Rufus appears later in the New Testament and, very possibly, is the son of Simon. I like to think that Simon, after having unwillingly carried the cross, was eventually overwhelmed by the grace of being so close to Christ that he came himself to embrace the faith and become a disciple. That would explain how Rufus became a convert, as mentioned by St. Paul. Perhaps the family of Simon were among those baptized on Pentecost. The Acts of the Apostles say that people from Cyrene were among the first to be baptized by St. Peter and the apostles on Pentecost.

It is not hard to imagine Simon of Cyrene, as an old man, telling his children and grandchildren about how the worst day of his life turned out to be the best. The pain and humiliation of being singled out to become part of a public spectacle around the execution of a criminal turned out to be the most beautiful moment in his life, because at that moment he was helping the Messiah to carry the cross, the instrument of our salvation, all the way to Calvary.

Even though Simon began carrying the cross begrudgingly, I’m sure there was a turning point, a moment in his life when he realized that carrying the cross was his greatest accomplishment, the greatest grace, and a turning point in his life.

I wonder if this coronavirus crisis is not the cross that we are being asked to carry. Like Simon, we can feel like our lives are upended, thrust into a situation that is not of our making. And yet this experience of the cross can also be transformative in our own lives, helping us to overcome our self-centeredness and be more other-directed, helping Jesus carry the saving cross when we reach out with compassion and empathy. This is a cross that teaches us humility and patience, and hopefully, how to put others first.

Hopefully, there will be a moment when we can look back at our history and say that this terrible scourge that caused so much suffering will have made us better people, more loving, more generous, more courageous, less materialistic, less individualistic, less self-centered. And hopefully, we will have the joy to be able to say that when I helped my brothers and sisters to carry their cross, I carried the cross of Jesus and became a real disciple.

Another secondary figure in the passion story is that of Joseph of Arimathea. Joseph would have been a wealthy Pharisee, politically connected, and an admired leader in the community. He was not like the poor working-class fishermen and farmers who were the typical followers of Jesus. Joseph of Arimathea, like his fellow Pharisee, Nicodemus, tried to follow Jesus at a safe distance. He felt inspired by Jesus’s message and was excited by his vision, but Joseph of Arimathea had much to lose if he were to be too identified with Jesus. In today’s jargon, he might be called a closet Christian. But all of that changed with the crucifixion. The apostles, with the exception of young John, all fled from Calvary. They ran away from the cross.

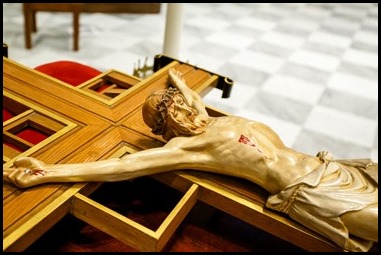

Joseph of Arimathea, on the other hand, was transformed by the powerful experience of the cross. He and Nicodemus were like those Israelites in the desert when the serpents were attacking God’s people. God told Moses to put a bronze serpent on a pole and that everyone who looks on that bronze serpent would be cured. The bronze serpent, of course, prefigured Christ raised on the cross. In the case of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, when they looked at the cross, they were cured of their self-importance, their cowardice, their vanity, their insecurities. Instead of running away from the cross, they ran toward it. We often use that image to describe our first responders, who rush toward the burning building, the bomb site, the COVID-19 ward.

The apostles had fled the scene into the witness protection program, and Jesus’s body would have been taken down and thrown in a common ditch, food for jackals and birds of prey, had it not been for this Pharisee who was transformed by the side of the cross, throws caution to the wind and rushes in to claim the body of Christ. He put the body in his own tomb. Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb becomes the first Tabernacle, holding the body of Christ.

When Joseph of Arimathea saw the cross, he saw the injustice, the persecution of a good and holy man. Today, when we listen to Christ’s passion, we hear the story of how much our God loves us, so much that he is willing to step in front of the bullet to save us. St. Francis calls the cross his book. In that book, he reads the greatest love story ever told.

With Palm Sunday, we begin Holy Week, when the Church is inviting us to relive the great events of the history of our salvation. This year I hope that we will see the cross in a different light. I pray that like Simon of Cyrene, we will find meaning in helping our brothers and sisters to carry their crosses, to endure their sufferings. I pray that like Joseph of Arimathea, we will overcome our fear and our pride and run toward the cross to proclaim to the world that we are the disciples of the crucified one. We love his sacred body, which is given to us as food, and we love the body of Christ that is God’s people, his Church.

The Gospel begins with the crowd waving their palm branches and welcoming Jesus. As always, our task is to work so that that crowd will become a community that will truly welcome Jesus as our Messiah and King and serve him in the least of our brothers and sisters. Crowds push people away from God, communities draw them closer to God. The virus keeps us from being under one roof, but that does not keep us from being a community. Our love for Christ and for one another is what makes us Christ’s body, the Church.

Together let us enter the Jerusalem of Holy Week, following Jesus, not at a safe distance but up close.

During the week, I have continued to attend remote meetings with the auxiliary bishops, vicars and members of our staff. I’ve also tried to reach out to as many of our people as possible.

We are so grateful for the technology that has enabled us to maintain a great deal of contact with people, even though we are unable to be personally present at meetings and individual celebrations.

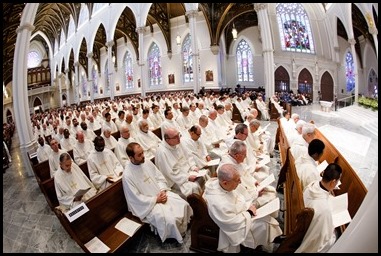

One of the strangest aspects of Holy Week this year for me is the lack of a Chrism Mass. The Chrism Mass is traditionally held on Holy Thursday. However, in recent years the Holy See has given permission for it to be moved to another day of the week when more priests are be able to be present. Here in Boston, we have a tradition of celebrating it on Tuesday of Holy Week.

The presence of the priests at that Mass is so important because together we bless the oils that will be used for the administration of the sacraments — baptism, confirmation, anointing of the sick and holy orders. It is also a time when the priests renew their promises of ordination.

So, this year, instead of just moving it earlier in the week, we will move it to the summer when, hopefully, we will be able to gather the priests together at the cathedral for the renewal of their promises. Although we are not having a Chrism Mass during Holy Week this year, I have recorded a message to the priests of the archdiocese that I would like to share with you here:

Although we are not having a Chrism Mass during Holy Week this year, I have recorded a message to the priests of the archdiocese that I would like to share with you here:

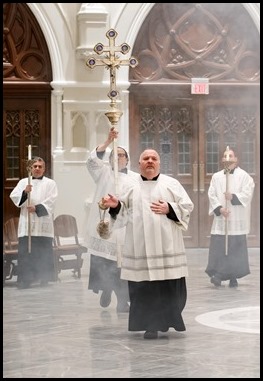

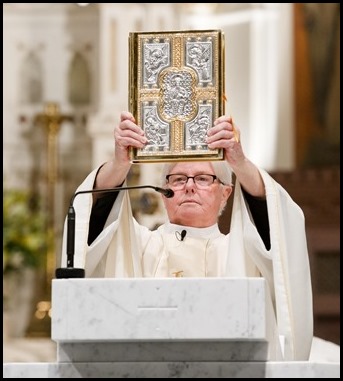

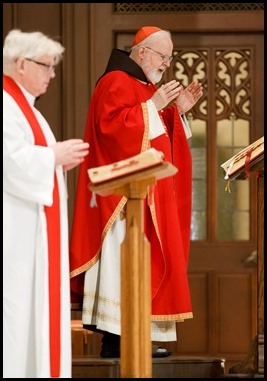

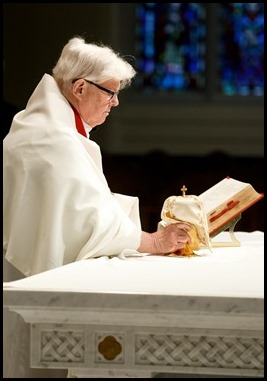

Holy Thursday, we began our celebrations of the Triduum with the Mass of the Lord’s Supper at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross.

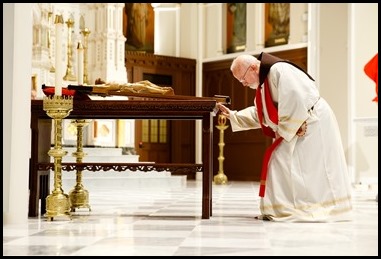

Because of the lack of the congregation, the celebration was simpler than usual this year. For example, there was no Washing of the Feet or procession to the altar of repose. Instead, there was an abbreviated time of adoration at the altar of the cathedral.

Also, we would have traditionally had a full chapel for the Eucharistic vigil until midnight. Normally, many of those who attend the vigil are students from the Boston University Catholic Center. Those we were unable to gather in person, I please we could meet together virtually that night.

Also, we would have traditionally had a full chapel for the Eucharistic vigil until midnight. Normally, many of those who attend the vigil are students from the Boston University Catholic Center. Those we were unable to gather in person, I please we could meet together virtually that night. This Mass was to have begun our celebration of the year of the Eucharist in the Archdiocese of Boston, but that has now been delayed until the feast of Corpus Christi in June. Like so many other things, we hope that by that time it will be possible for our people to gather with us for that very special event.

This Mass was to have begun our celebration of the year of the Eucharist in the Archdiocese of Boston, but that has now been delayed until the feast of Corpus Christi in June. Like so many other things, we hope that by that time it will be possible for our people to gather with us for that very special event.

Our Good Friday observance also was different in many ways this year. Normally, during the day, we have the Way of the Cross For Life and the Stations of the Cross of Communion and Liberation visit the cathedral, as well as the Living Stations of the Cross done by the Hispanic community of the cathedral. Then, in the afternoon, we would have the full celebration in English and then the liturgical celebration in the evening in Spanish.

This year we had only the English celebration at 3 p.m., with the solemn proclamation of the Passion, the Veneration of the Cross and the Communion service.

I’m very impressed by the large number of people who are participating in our Holy Week liturgies through television or online. It is a clear indication that a hunger for contact with the Church and a desire to participate in the sacred mysteries of Holy Week is very much alive in the hearts of our people. Once again, I’m very grateful to our priests and parish leaders, who have been so creative and energetic in devising ways of getting the message of the Church out and allowing people to have a sense of belonging to their communities during this time.

Wishing a blessed and safe Easter,

Cardinal Seán