Hello and welcome,

Certainly, immigration is such an important theme in the life of the Church — not just in the United States, but throughout the world. This is a time when there are more refugees than at any point since World War II, and many people are suffering. We, as Americans and Catholics, need to reflect on what our role should be in trying to find a drug and to bring relief and justice to so many people who are in this very dangerous and precarious situation.

Because this theme is such an important one in the life of the Church, I wanted to share some of my reflections with the people of Boston. So, I submitted this piece to the Boston Globe this week, which I would also like to share with you here:

Immigration is as ancient as recorded history. It is driven by multiple factors — people move because they are afraid, oppressed, or to escape violence and chaos. Immigration is often accompanied by human tragedy. But not always — people also move because of hopes and dreams. They move to find new opportunities, and they move to contribute to their new country. Having worked with immigrant communities throughout my priesthood, I have seen how deeply patriotic they are when they are welcomed to this country.

Immigration in our time has far exceeded previous experience. The World Health Organization estimates that one billion people are migrating today. We live in a globalized world; in that context, movement is perpetual. Ideas move, products move, money moves. But people do not migrate easily. Obstacles abound.

Part of the reason is that our globalized world is structured and governed by sovereign states. It is a basic function of states to establish secure boundaries, defining the territory where they exercise sovereignty.

Security and sovereignty are part of the reality of immigration, but they are not all of it. Sovereignty has moral content, but it is not an absolute value. The immigration policy of states should combine security with a generous spirit of welcome for those in danger and in need.

That necessary combination of values is seriously lacking in the United States today. Principal responsibility for this moral failure must rest with the federal government, where policy is a product primarily of the president and Congress. But it also must be recognized that, as a society, we are deeply divided over immigration. Our divisions have produced severe human consequences — it is imperative to acknowledge some of them.

First, the most dramatic and dehumanizing consequence is to be found on the border with Mexico. To be sure, the challenge — thousands of adults and children seeking asylum every day — is unprecedented in recent history. But even a challenge of this severity, in a country of our resources and capabilities, cannot justify how these children and families are being treated. The overarching policy of the US government lacks justification.

Rather than a humane plan, existing policy in word and deed is more focused on castigating and confining young and old, male and female, in conditions often pervasively unfit for human life and dignity.

Second, rather than focus the efforts of all relevant agencies on the relief of suffering at the border, there are continuing threats made that the government will scour the country to remove people who have settled here and whose children are citizens.

Third, the dysfunction of our policy is acknowledged across the political spectrum of our country. The crisis at the border and the focus on removals leave the broader policy agenda unresolved in the executive and legislative branches of government.

To be sure, there are thousands at the border who require immediate attention. But there are also 11 million unauthorized immigrants in our midst with no policy to stabilize their existence and provide a path to citizenship — a policy objective advocated by the Catholic Church for decades.

Among the 11 million people are 3.6 million people brought to the United States as children, of which only 700,000 have temporary protection from deportation through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which is itself under threat. There are also over 400,000 people with Temporary Protected Status who are living in limbo. They have come to the United States for various reasons — for some, their countries have suffered natural disasters and they have no viable option to return home. There are no policies in place to allow TPS holders, the majority of whom have lived in the United State for more than 20 years, to earn lawful residency and move forward in their lives.

The point of identifying these broad categories and consequences of existing policy is to highlight that practical, concrete choices are available to correct a dysfunctional policy. First, we should recognize that economic assistance to El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Haiti, and Mexico could assist people to remain in their home countries. In addition, the historic “guest worker” program, which provides temporary visas for workers, can contribute to the needs of the United States as well. However, our policies on Central America seem exclusively focused on threats, coercion, and punishment. This is surely misguided.

Developing positive solutions does not seem to be the motivating concern of existing policy. Instead, the current emphasis, we are told, is on “deterrence,” a term at home in military policy that is now being advocated to confront people with no power of any kind. The targets in this case are not an armed array of hostile attackers. They are women, children, families.

Fourth, while deterrence can have some role in law enforcement and has been used by other administrations, much depends on the spirit and motivation that animates our broader immigration policy. Current US policy and practices combine to project an attitude of animus toward immigrants. Most evident is the language used at times to describe people on our borders; it is often degrading and demoralizing.

Beyond language, there are the policies to reduce the number of refugees the United States will welcome. The numbers have been reduced substantially, and threats exist to reduce them to zero. The federal government recently announced it will expedite removals of undocumented immigrants without judicial appeal or oversight and move to provide for unlimited detention of families seeking asylum. The tenor, tone, and result of these policies communicate a distinct message: We have no room in our hearts and no space in our country for people facing life-and-death situations. This hostile spirit toward immigrants extends to proposals to expel some of those receiving crucial medical care. A similar spirit of lack of compassion and generosity is manifested in new proposals to focus immigration increasingly on merit-based applicants, leaving the poor excluded.

Our present moment requires civility and charity among the citizens of our society and toward those hoping to become citizens. As a country it is a good time to remember the biblical axiom: To whom much is given, much is expected.

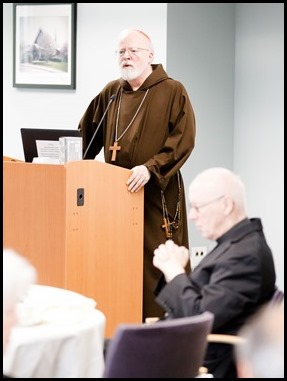

Last Friday, we had our annual gathering of newly retired priests at the Pastoral Center.

In the morning, they heard a presentation by Joe D’Arrigo and his staff of our Clergy Health and Retirement Trust, providing them with helpful information as they make the transition to the role of Senior Priest. Then, at noon, I joined them for lunch.

It was a wonderful opportunity to thank them for their service and give them a small token of our appreciation.

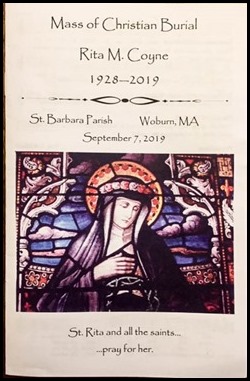

Saturday, I attended the funeral Mass of Rita Coyne, the mother of Bishop Christopher Coyne of Vermont, at St. Barbara Parish in Woburn.

Rita Coyne had worked as the parish secretary at St. Barbara’s for many years and her family was very much involved in the life of the parish. Rita had a very large and close-knit family, and many of her family and friends gathered for the celebration of her funeral Mass. Also with us was Bishop Libasci of New Hampshire, along with many priests and parishioners.

Bishop Mark O’Connell, who was a young priest at St. Barbara’s during Rita’s time as secretary, gave the homily and, of course, Bishop Chris Coyne was the principal celebrant. At the end of the Mass, Bishop Coyne reflected on the importance of the parish to his mother and his family – the site of so many his family’s baptisms, first communions, confirmations, weddings and funerals.

On Sunday, I went to St. Mary of the Assumption Parish in Lawrence to join in their celebration of Nuestra Señora del Cisne, which in English is “Our Lady of the Swan.”

The name comes from town of El Cisne in the province of Loja, Ecuador. The tradition says that, in the late 1500s, the people of El Cisne desired to have their own image of the Blessed Mother to venerate. So, they traveled to the capital city of Quito and arranged for an artist carve a statue of Our Lady out of cedar, which they brought back and placed in a small shrine.

Then, in 1594, there was a terrible drought that led to a famine, and the people thought that they would have to abandon their town to survive. As they prepared to leave, the people came to pray before the image of the Virgin to ask for her protection as they fled. But Our Lady appeared to them and told them not to leave and that, if they remained, built a church and stayed faithful, she would watch over them. Shortly thereafter, the rains came and restored fertility to the land.

Our Lady of El Cisne has been a very popular devotion of the Ecuadorian people ever since. I was reading that Simón Bolívar, the great figure of Latin American history, was among those who have made a pilgrimage there.

They had the church decorated with the colors of the Ecuadorian flag and the beautiful image of Our Lady of El Cisne. It was a beautiful celebration.

There was a great turnout of the Ecuadorian community for the Mass, and many of them were wearing the traditional dress of the different regions of Ecuador. We were also honored to have the consul general of Ecuador in Boston, Beatriz Almeida de Stein, join us for the celebration.

The celebration ordinarily coincides with the Feast of the Assumption. However, they chose to celebrate it on September 8, the Feast of the Nativity of Our Lady. In fact, in Latin America, many of the Marian feasts are celebrated on that day. As I told the people, my first public Mass was on September 8, a Mass for Our Lady of Caridad del Cobre celebrated with the Cuban community of Washington at St. Matthew’s Cathedral.

There was a huge crowd of between 1,200 and 1,400 people, and afterwards there was a lovely gathering in the parish hall.

We are very grateful for the fine work of the administrator, Father Israel Rodriguez who, along with Fathers Maciej Araszkiewicz and Ignacio Berrio, stepped in at a time when the parish was in great need after the departure the Augustinians who had ministered there for a century. By all accounts, the parish is thriving.

It has always been one of our most active parishes, and so it is always a joy to visit them and celebrate Mass with the community.

That evening, I had dinner at the cathedral with Jim Towey, the president of Ave Maria University, who was in town and came to greet me.

I am always happy to hear the latest updates on the goings-on at Ave Maria, and we are grateful for the wonderful work that Jim and his team are doing there.

One of their programs that I find particularly interesting is Ave Maria’s Mother Teresa Project, a center dedicated to the life and work of Mother Teresa, which takes students around the world to visit the Missionaries of Charity in their different missions. It is really the only center of its kind dedicated to Mother Teresa’s legacy. The center came out of Jim’s long collaboration with Mother Teresa — he had been Mother Teresa’s lawyer for about 25 years. (When people ask him why Mother Teresa had a lawyer, he always jokes, “Because she liked to sue people!”)

On Tuesday, we had a luncheon meeting of our Vicars Forane in the Archdiocese of Boston.

We began our gathering with midday prayer.

Then we heard a presentation by Sean Hickey and Father Paul Soper of our Pastoral Planning Office, after which we had a time of dialogue between myself and the vicars.

We are very grateful for the work that they do, providing leadership in the different regions of the archdiocese, particularly in bringing the priests together to reflect on the important issues and policies that reflect the life of our Church.

We have organized the Presbyteral Council in such a way that the priests from our vicariates are represented on the Council and have an opportunity to engage in conversations about themes that are being discussed and decided upon at the Presbyteral Council. In this way, we have the input of priests throughout the archdiocese.

So, the work of the Vicars Forane is very important in promoting fraternity among our priests and gathering them together in prayer and reflection, so that we can have an intentional presbyterate where people are part of the decisions that are being made that affect the life of our Church.

Finally, of course, this week we marked the 18th anniversary of the attacks of September 11, 2001. We prayerfully remember those who lost their lives, the first responders, and all those who were affected by the attacks.

Just recently, I had an opportunity to visit the memorial at Ground Zero in Manhattan and was so impressed by how many people go there and what an important tribute it is to all those who lost their lives there and to those who so courageously came to their aid. All of us who lived through it know how deeply people’s lives were affected by this terrible tragedy.

We live in a world where there is so much violence and hatred. Let us all strive to be instruments of peace in the world, so that these kinds of acts of wanton violence can be overcome by our spirit of solidarity and shared humanity.

Until next week,

Cardinal Seán