Hello everyone and welcome back!

This has certainly been a very busy week filled with many wonderful events, both in here in the archdiocese and in Washington, surrounding the March for Life.

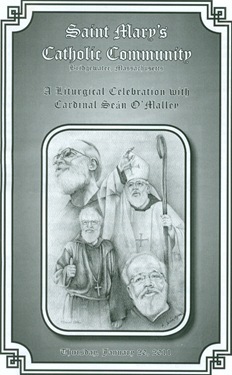

Let me begin by mentioning that last Thursday we had Mass at the Old Colony Correctional Center in Bridgewater.

Deacon John McHough is in charge of the prison ministry there and he is doing such a great job. The Catholic community there is so vibrant.

The program for the Mass featured drawings done by one of the prisoners.

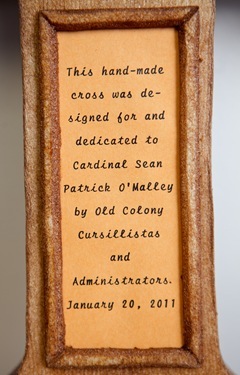

They also gave me some nice gifts to commemorate my visit.

There was this wonderful cross, which they made for me.

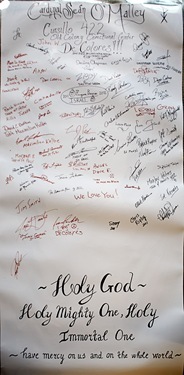

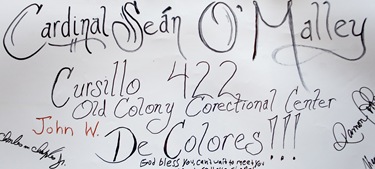

They had also just had a Cursillo a couple weeks before. So they gave me a large picture of the Divine Mercy with signatures and messages from the Cursillistas on the other side. It’s probably hard to tell here, but it’s about 6 feet tall!

– – –

That evening, we had a very large group — about 70 young men — for a St. Andrew’s Dinner and Holy Hour.

Periodically we host these St. Andrew’s dinners to bring together young men who may be considering the priesthood. It is a chance for our young men to meet our seminarians and begin a process of discernment.

There were group from a number of different parishes. Here I am with the group from Sacred Heart in Lynn

I was very happy to be able to spend the evening with all of them.

– – –

On Saturday, we ordained seven transitional deacons in a beautiful Mass at the Cathedral: Deacons Thomas Cannon, John D’Arpino, Michael Farrell, Sean Hurley, Kwang Lee, Mark Murphy and Carlos Suarez.

Five of the men were from the archdiocesan seminaries, Brother Sean was from the Franciscans of the Primitive Observance and Brother Thomas was from the Oblates of the Virgin Mary.

During my homily I reminded them that in the New Testament the Apostles are called the twelve and the deacons are called the seven, so this was a very propitious number!

You can hear my whole homily here:

It was a wonderful turnout despite the residual effects of the snowstorm from the day before.

I ask you to keep these men in your prayers as they prepare for their ordination to the priesthood in the spring.

– – –

That afternoon, I departed for Washington, D.C. to be with our young people and seminarians at the March for Life.

On Sunday, I had lunch with the seminarians of Blessed John XXIII National Seminary in Weston.

They had come down a little early and had a chance to see some the historic sites of the city before the official March events began that evening.

After our lunch, I made a quick trip to visit an old friend who had been ill, Mongo Dominguez, and his wife Carmencita.

As we were leaving I realized we were very close to home of Cardinal Baum, whom I have known since his time as Archbishop of Washington before leaving to serve in Rome for many, many years. (When I started in Washington, Cardinal O’Boyle was the bishop, then Cardinal Baum, and then Cardinal Hickey.)

I decided to make an impromptu visit and Cardinal Baum was very gracious to receive us on such short notice.

We had a wonderful visit and it was good to see that despite some health challenges, the cardinal still has a wonderful spirit.

During my visit, we also had a dinner with a group of Cuban friends at the home of Manela and Tony Diez.

– – –

In the evening, we had the Vigil Mass for Life at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception.

Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, the president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ pro-life committee, preached and presided at the Mass.

It’s always impressive to see the procession of priests and seminarians, which took over a half hour.

There were also about 40 bishops in attendance.

The Mass was absolutely jam-packed, so much so that many of our young people were sitting on the floor and in any nook and cranny of the basilica they could find. They offered the Mass on closed-circuit television downstairs, and many, many people had to watch it there. You might say it was beyond standing room only!

– – –

Monday was the March itself, and the groups participating try to begin the day with a Mass. Many of the groups go to a downtown arena, the Verizon Center, which holds around 30,000 people.

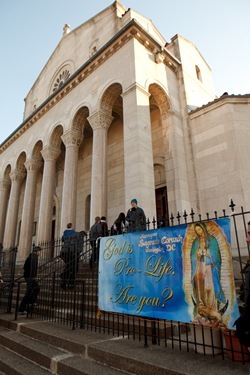

However, the numbers of people attending has grown so much in recent years that they are having satellite Masses as well. So, that morning all the groups from Boston met for a Mass at Sacred Heart Church, the Capuchin church where I had worked as a young priest celebrating Mass for the Hispanic and Haitian communities.

It’s a beautiful old church that was, at one time, a candidate to serve as the Cathedral of Washington.

In my homily, I told the young people that during the time of the riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, I had lived in the basement of that church with 700 people for about a week.

During that time, a baby was born. I took the mother to the hospital in an Army jeep because there was a curfew. There were tanks all around the White House and soldiers with bayonets on the street corners.

They named the baby after me. The family was from El Salvador and I said I felt so bad because I was sure no one in his family would be able to pronounce it!

We were grateful to the friars and the staff for accepting us, particularly the pastor, Father Moises, who was a wonderful host.

– – –

Immediately following the Mass, the parish provided lunch for us and we went on to the March for Life.

I marched with the seminarians from St. John’s. We had over 100 seminarians come down from Boston.

The St. John’s group was so large that they chartered their own Amtrak car! It was the first time they ever did that and I understand it was a great experience.

The March is so important, particularly for us as Catholics.

It has been held each year since 1974, the year after Roe vs. Wade was decided.

Every year hundreds of thousands of concerned Americans have descended on Washington to show their belief that abortion is an affront to the dignity of human life.

The Catholic community has taken a particular interest in this gathering because it witnesses to the fact that all human life is sacred, from conception until natural death. It is one of the most fundamental teachings of our Catholic faith.

We are all called to build a culture of life in our world and promote a more just society.

We probably had at least 400 people from Boston all told. There were over 100 seminarians and almost 300 youth and young adults.

As I like to say, the experience is something like a mini-World Youth Day. I think it’s so good for our young Catholics to experience the vibrancy of the Church when so many young people are involved in the liturgies and witnessing to the Gospel of Life.

We’re very, very grateful to the schools and the parishes that made it all happen.

We are particularly grateful to Father Matt Williams and the entire staff of our Office for the New Evangelization of Youth and Young Adults for organizing the trip for our young people — middle and high school students as well as our young adults.

– – –

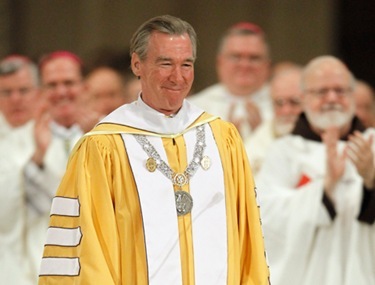

On Tuesday, I was back at the National Shrine for the installation of John Garvey as president of Catholic University of America. As many of you know, he was the dean of the Boston College Law School before accepting this post.

John is truly a gifted intellectual and a man whose life is profoundly Catholic and faith-filled. I know he will do much to continue to deepen the Catholic identity of the Catholic University of America.

For the first time, the installation of the new president took place in the context of a Mass. After the homily by Cardinal Wuerl, who is the chancellor of the university, he was installed by Archbishop Allen Vigneron of Detroit, the president of the Catholic University board.

President Garvey then made his Oath of Fidelity and led the congregation in praying the Creed as part of his profession of faith. It was a very moving moment.

At the end, he gave a stunning inaugural address on the relationship between virtue and knowledge and the importance and meaning of Catholic education.

I leave you this week with the text of his address. I recommend it to all of you!

Until next week,

Cardinal Seán

Intellect and Virtue: The Idea of a Catholic University

John Garvey, President, Jan. 25, 2011

I have been thinking a lot about Cardinal Newman this year. He was beatified in September, and that’s something for academics to celebrate. (We rarely warrant such attention from Holy Mother Church.) He was a Cardinal, and now so am I. He was the first rector of the Catholic University of Ireland, which opened its doors in 1854. Here am I now, president and rector of The Catholic University of America, begun two decades later.

I have in my office a letter Newman wrote to Cardinal Gibbons back then. He says

At a time when there is so much in this part of the world to depress and trouble us as to our religious prospects, the tidings which your circular conveys of the actual commencement of so great an undertaking on the other side of the ocean . . . will rejoice the hearts of all educated Catholics in these Islands.

Newman thanks Gibbons and the board for “introducing into their appeal a quotation from what I wrote years ago upon the subject of universities.” He is referring to The Idea of a University, discourses delivered when he became rector of the Catholic University of Ireland.

Thinking I might learn something to the purpose, I turned to them with interest. The first thing I noticed was how much we disagreed. Newman thought it was not the business of a university to extend the boundaries of knowledge. “To discover and to teach,” he says, “are distinct functions; they are also distinct gifts, and are not commonly found united in the same person.”1 The Catholic University of America was begun strictly as a graduate research institution, after the pattern of the ancient Catholic University of Louvain, or closer to home, the Johns Hopkins University begun in 1876.

Newman defended the idea of a liberal education – a notion I heartily endorse. But he thought that imparting scientific, technical, and professional knowledge was not the business of a university. He had one foot in the Oxford of the eighteenth century, and on this point too we part company.

Then there is his nineteenth century prose. It’s a style I loved in my youth (when I also loved Chopin and Turner and Melville). But it doesn’t work for lawyers. Legal ideas are hard enough. You can’t let your writing compete with them for the reader’s attention. You won’t catch me writing a sentence like this:2

How much more genuine an education is that of the poor boy in the Poem – a Poem, whether in conception or in execution, one of the most touching in our language – who, not in the wide world, but ranging day by day around his widowed mother’s home, “a dexterous gleaner” in a narrow field, and with only such slender outfit

“as the village school and books a few/Supplied,”

contrived from the beach, and the quay, and the fisher’s boat, and the inn’s fireside, and the tradesman’s shop, and the shepherd’s walk, and the smuggler’s hut, and the mossy moor, and the screaming gulls, and the restless waves, to fashion for himself a philosophy and a poetry of his own!

But there is one point we agree on. Newman’s first four discourses are an argument for the place of theology in the university curriculum. By theology he meant not “acquaintance with the Scriptures” but everything “we know about God.”3 In Ireland at the time there was a fight going on about ‘mixed education’ (Catholics and Protestants). Trinity College, like Oxford, was an Anglican institution where Catholics were not welcome. To quell the rising Catholic resentment at this exclusion Peel’s government introduced a bill in Parliament to create three Queen’s Colleges (Belfast, Cork, and Limerick). They would have no religious test for admission; nor would religion figure in the curriculum. The Irish bishops, and Newman, resisted this approach. The new Catholic University of Ireland was their proposed solution. And The Idea of a University is an argument for why it was necessary.

Fast forward now 150 years. The mixed or secular model of education is the norm in America. In public schools we say the Constitution requires it. In private schools, where the first amendment does not apply, faith is unwelcome for epistemological reasons. Whether it is emotion or fantasy or paranormal perception, it is (we suppose) different from serious thinking – a distraction at best; probably misleading. In this view of things The Catholic University of America has ambitions (to be Catholic and to be a university) that are in conflict with each other.

Our discussions of this subject have a two-dimensional character, and this is the point I want to address today. We speak of an opposition of faith and reason, as different ways of knowing. The self-styled advocates of reason say we come to know things through processes of induction and deduction, the methods of science and logic. They describe faith as a commitment to divine revelation, usually found in scripture, though it might be read in the book of nature. The battlefront lies along two propositions of physics and biology – how the universe and human life came to be.

· Genesis tells us God created the world from nothing.

·

· Stephen Hawking says the world created itself from nothing.4

·

· Genesis tells us God created man on the sixth day.

·

· Stephen J. Gould says man evolved over a very long time from simpler forms of life.5

·

The story of this war is so familiar that we often redescribe the conflict of faith and reason as a conflict of religion and science. And the challenge for Catholic universities is finding a place for bibles and papal decrees between our telescopes and microscopes.

I think the fault for this flat, crabbed, cartoonish vision of Catholic higher education lies not with the critics of religion but with us. We have been so intent on defending ourselves against charges of fundamentalism and censorship that we have failed to create, let alone promote, a serious Catholic intellectual culture. Think of the schools of thought we have seen come (and go) in the academy in our lifetimes: Marxism, modernism, post-modernism, feminism, law and economics, critical race theory, queer theory, and so on. And ask yourself whether, in the Catholic intellectual tradition, there is not enough material to get our own movement going.

Here are two steps we might take in that direction. First, let us bracket the virtue of faith, and consider the role that other virtues might play in our intellectual life. Second, let us consider the contribution that Catholic intellectual culture might make outside the field of science. Or to compress both points into one proposition, let us look at the interplay of intellect and virtue across the full field of university life.

The Role of Virtue in the Intellectual Life

My wife and I have sent our five children to Catholic schools from kindergarten through college. In some ways their college education was the most important part of their formation. We hoped that, in the right environment, they would grow in wisdom, age, and grace. We wanted their schools to provide a nurturing sacramental life. We wanted our children to discern their vocations, in married or religious life, in the company of friends and teachers who loved God and the Church.

This suggests, if we examine practice and not theory, that one mark of a Catholic university is the nature of student life. A Catholic university should be concerned with the formation of its students. Campus ministry, residence life, service opportunities, athletics, student activities, are an integral part of our mission. The measure of our success is how our graduates live their daily lives: do they pray and receive the sacraments; do they love the poor; do they observe the rest of the beatitudes?

They Are Connected

You’re probably thinking that I digress already. But we and Cardinal Newman thought alike. One of my favorite sermons, from his time in Ireland, he preached on the feast of St. Monica, the first Sunday of their school year. Like the Garveys, Monica watched her son Augustine go off to college in Carthage. There he fell into bad company and bad habits. Newman says,

Bad company creates a distaste for good; and hence it happens that, when a youth has gone the length I have been supposing, he is repelled . . . from those places and scenes which would do him good. . . . So he begins to form his own ideas of things, and these please and satisfy him for a time; then he . . . tires of them, and he takes up others; and now he has begun that everlasting round of seeking and never finding; at length . . . he gives up the search altogether, and decides that nothing can be known, and there is no such thing as truth[.]

The problem arises, Newman observes, when we make the mistake of separating intellect and virtue. And returning to our subject, he concludes

Here, then, I conceive, is the object of the Holy See and the Catholic Church in setting up Universities; it is to reunite things which were in the beginning joined together by God, and have been put asunder by man. Some persons will say that I am thinking of confining, distorting, and stunting the growth of the intellect by ecclesiastical supervision. I have no such thought. Nor have I any thought of a compromise, as if religion must give up something, and science something. I wish the intellect to range with the utmost freedom, and religion to enjoy an equal freedom; but what I am stipulating for is, that they should be found in one and the same place, and exemplified in the same persons.

But what, you may ask, is the connection? Sure, Monica wanted to reform Augustine’s behavior. But what bearing would that have on his intellectual life? Aren’t we committing a sort of category mistake in supposing the two to be related? That is the received wisdom in some quarters. Consider the observation of John Mearsheimer, the Wendell Harris Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago:6

Today, elite universities operate on the belief that there is a clear separation between intellectual and moral purpose, and they pursue the former while largely ignoring the latter. There is no question that the University of Chicago makes hardly any effort to provide you with moral guidance. Moreover, I would bet that you will take few classes here at Chicago where you discuss ethics or morality in any detail, mainly because those kind[s] of courses do not exist.

That was ten years ago. Today teaching ethics is all the rage. In 2009 Harvard Business School proudly announced an effort by its graduating students to get classmates to sign the MBA Oath, a pledge to act ethically in the business world. Students pledge to refrain from corruption, unfair competition, and harmful business practices; to protect human rights; and to set an example of integrity. Last fall Harvard announced a gift of $12.5 million to fund a five-year cross-disciplinary effort to study ethics and institutional corruption. The intriguing thing about this is that at Harvard there is a connection between the oath and the study, between the cultivation of virtue and the intellectual life. What is it?

Does Intellect Lead Us To Virtue?

Academics like to think that intellect is the key thing – that if we know the good we will cultivate and pursue it. This is not surprising. Academics are intellectuals. Thinking is what we are good at. Abraham Maslow once said if you only have a hammer, every problem begins to look like a nail. But there are two difficulties with the academics’ approach. One is that it fails to account for weakness of will. We all have the experience of knowing what is right or good, and failing to do it. (I have this problem about chocolate.) The second is that it flattens the concept of knowing into something most of us wouldn’t recognize. We do not come to understand what is right, or good, or beautiful, through mental exercises conducted from an armchair.

Aristotle observed, what every parent knows, that young people can develop abilities in geometry and mathematics, but they can’t be proficient at politics, or philosophy, or (he says) physics, because “the first principles of these other subjects come from experience, and . . . young [people] have no conviction about the latter but merely use the proper language.”7 I am reminded of my own experience in Louis Jaffe’s class in Administrative Law – a subject about the role, processes, and powers of government agencies. I got an A in the class by saying the right things, but it was like a game in a foreign language I had memorized but did not speak. I had no idea what the subject was about until, 10 years later, I represented dozens of agencies as a young lawyer in the Solicitor General’s Office. I remember thinking, “So this is what Administrative Law is about.”

Part of what I had learned was the objects and practices that the foreign language denoted – what it meant to publish a notice of proposed rulemaking in the Federal Register. That connected the purely intellectual exercise of reading Jaffe’s casebook to things in the real world. Another part of what I learned was the craft of doing administrative law well. A baseball pitcher needs to learn a lot of mechanics to throw well; a fielder needs to be in the right position for each hitter and situation. So too with learning the law. Good administrative lawyers know from practice that agencies must follow their own regulations (the Accardi8 rule). Richard Nixon ignored this when he refused the special prosecutor’s demand for the Watergate tapes.

There is a third thing one learns from the experience of legal practice – it acquaints one with the virtue of justice. A good lawyer is not just skilled in the craft of argument. She is also honest, fair, prudent, temperate, and just. There is an inscription on the Department of Justice building where I worked that says, “The United States wins its case whenever justice is done one of its citizens in the courts.” Working with good lawyers, you learn there are cases you could win but should not. You learn the difference between playing by the rules and doing the right thing. You are reminded that the agencies whose behavior is regulated by administrative law exist to serve the people of the United States (veterans, homeless, unemployed, widows and orphans, victims of crime, consumers, taxpayers), and you are one of the people standing at the counter.

St. Bonaventure, in his little treatise Bringing Forth Christ, observes9

“Anyone who keeps close to a holy man discovers that by seeing him often, listening to his words and witnessing his exemplary behavior, he is set on fire with love of the truth, keeps away from the darkness of sin, and is inflamed by the love of divine light.” . . . “Seek the company of good people. If you share their company, you will also share their virtue.”

We come to know virtue by seeing it, we learn virtue by practicing it, we become virtuous when our practice makes it habitual, a part of our character.

Virtue Guides Intellect

Let us return to Aristotle and our theory of education. He goes on to say that if you want to listen intelligently to lectures on ethics you “must have been brought up in good habits.”10 It is virtue that leads the intellect to the right result, not the other way around. The particular goals we set for ourselves are illuminated by our character or moral orientation. In our efforts, Aristotle says, “virtue makes us aim at the right mark, and practical wisdom makes us take the right means.”11

Aristotle talks about listening intelligently to lectures on ethics, but his point is not limited to Philosophy 101. I spoke earlier about Law. I might have said the same thing about any of the social sciences. You cannot study migration, the environment, the economy, interpersonal relationships, death and dying, or the history of capitalism without making ethical judgments of the kind Aristotle had in mind. Sociology is not, pace Comte, a value-free science. Nor is Anthropology, Economics, Psychology, or History.

I have been talking about the social sciences, but I might make a similar observation about aesthetics. Our appreciation of beauty in art and music, in poetry and architecture, is not just an intellectual judgment. We speak of the sense, the experience, the love of beauty, and these are not just metaphors. It is beauty that first enchants us when we fall in love, that draws us out of ourselves to want something other. And though there is more scope for taste in this realm, there are true and there are meretricious appeals of beauty, and we learn them not by solitary contemplation but in the same way we learn the appropriation of virtue.

Cardinal Ratzinger, a few years before he became pope, observed how some appeals can be like the “experience of beauty of which Genesis speaks in the account of the Original Sin. Eve saw that the fruit of the tree was ‘beautiful’ to eat and was ‘delightful to the eyes.’” “Who would not recognize,” he went on to say, “in advertising, the images made with supreme skill that are created to tempt the human being irresistibly, to make him want to grab everything and seek the passing satisfaction rather than be open to others.”12 He contrasted this with an experience he had in Munich soon after the death of Karl Richter. He was sitting at a Bach concert, next to the Lutheran Bishop Johannes Hanselmann, and when the performance was over he said,

When the last note of one of the great Thomas Kantor Cantatas triumphantly faded away, we looked at each other [and] said, “Anyone who has heard this, knows that the faith is true.”

The music had such an extraordinary force of reality that we realized, no longer by deduction, but by the impact on our hearts, that it could not have originated from nothingness, but could only have come to be through the power of the Truth that became real in the composer’s inspiration.

I have been arguing that the arrow between intellect and virtue travels in a different direction than scholars sometimes suppose. That the cultivation of virtue prepares the ground for the work of the intellect, because “virtue makes us aim at the right mark.” Let me give one more example. When we went off to college my mother would say, after the fashion of St. Monica, “Don’t forget your prayers.” After I got out of law school she came to visit me in New York, and I told her about a book I had just read (by J.N.D. Kelly, as I recall) on early Christian doctrine. I asked if she knew that the words “light from light” that we recited in the Nicene Creed were meant to resolve the Arian heresy about the relation between God the Father and God the Son. She said, “Dear, the important thing is not that you understand it. The important thing is that you believe it.”

The older I get the more I find that my mother was right. I don’t mean to embrace the full import of her observation. The Council of Nicea was really important, and it met to iron this out. But Mother was giving me the same advice she had when I went off to college: the most important thing is to say your prayers before you go off on your intellectual wanderings. Pascal said precisely the same thing in the Pensées,13 after describing the reasonableness of his wager:

The external must be joined to the internal to obtain anything from God, that is to say, we must kneel, pray with the lips, etc., in order that proud man, who would not submit himself to God, may be now subject to the creature. . . . [C]ustom . . . without violence, without art, without argument, makes us believe things and inclines all our powers to this belief, so that our soul falls naturally into it.

Mother, St. Monica, and Pascal were all saying that the path to the study of theology begins with prayer, not speculation. Or to return to the reflections of Pope Benedict, “the true apology of Christian faith, the most convincing demonstration of its truth against every denial, are the saints, and the beauty that the faith has generated.”14

The Institution’s Role

I have been arguing that the acquisition of virtue has a bearing on how we learn. This is a lesson all university students should take to heart. Students at the University of Kentucky should find the Newman Center. Harvard students should meet the chaplain at St. Paul’s Church. But this is an incomplete argument. What is the particular contribution a Catholic university makes to the integration of virtue and intellect?

Let me close with four brief observations about this point. First, although we sometimes speak (as Bonaventure does) of learning virtue from a holy man (a kind of moral Bruce Harmon, or yoga master), we learn it better as members of a group. As the Catechism says, the Christian “learns the example of holiness [from the Church;] he discerns it in the authentic witness of those who live it . . . .”15 Both the yogi and the group provide the necessary illustration. But it’s like learning a foreign language. No tutor alive can match the experience of living with a family that speaks Korean.

Groups have this additional advantage over yogis: besides offering round-the-clock instruction, they also provide a counterweight to the culture. In raising our children my wife and I have found that it is hard to fight the culture. We deliver one message about materialism, sex, self-sacrifice, and alcohol; our children see another in school and the media. Our lesson gains credibility if the children see a community of people they know and admire living it.

Second, as Christians we believe that the community we live in here is not just us. It is God with us, in the sacraments we celebrate every day. His grace is more important than our mutual example in helping us see and drawing us to the life of virtue.

Third, we must not lose sight of the essential connectedness of intellect and virtue. When Aristotle says that if you want to listen intelligently to lectures on ethics you “must have been brought up in good habits,” he does not mean simply that you must do a before b. (As we might say, if you want to get from Boston to Washington you must first go through New York.) The cultivation of virtue enables the student to learn what the teacher is teaching. It is part of the language they both speak.

To put it in concrete terms, Student Life, Campus Ministry, Residential Life, Athletics, and Student Organizations are not offices concerned with different parts of the day and places on campus than academic affairs. They are integrally related. As Pope Benedict said at this University in 2008, this “is a place to encounter the living God . . . . This relationship elicits a desire to grow in the knowledge and understanding of Christ and his teaching.”

Finally, I have been talking about the role of virtue in the life of the intellect. But I want to conclude by observing that the intellectual life of a Catholic university is something that is unique among institutions of higher education. Whatever your intellectual field, you are probably familiar with the phenomenon I might call the coffeehouse effect. Carl Schorske describes in his interesting book Fin de Siècle Vienna how intellectuals from many different fields gathered in the coffeehouses of Vienna at the turn of the twentieth century and created a special intellectual culture: Kokoschka and Schoenberg, Freud and Klimt, Mahler and Mach. We can see the same thing at other times and places. Elizabethan London was a city the size of Lubbock, Texas, and it produced Shakespeare, Marlowe, Spenser, Sidney, Jonson, and Bacon. Bach, Handel, and Telemann were all born around 1685 and studied each others’ work. The world’s best violins have all come from Cremona, Italy where they were made by the Amati, Guarneri, and Stradivari families.

The Catholic University of America is a university – a community of scholars united in a common effort to find goodness, truth, and beauty. It is a place where we learn things St. Monica could not teach her son. Holy as she was, she could not have written the Confessions or The City of God. Smart as he was, neither could Augustine have written them without the intellectual companionship he found first at Carthage and later among the Platonists in Milan. The intellectual life, like the acquisition of virtue, is a communal (not a solitary) undertaking. We learn from each other. The intellectual culture we create is the product of our collective effort. A Catholic intellectual culture will be something both distinctive and wonderful if we bring the right people into the conversation and if we work really hard at it.

Conclusion

Let me close as Cardinal Newman did his discourses on The Idea of a University. He ended with a note of fitting modesty about the contribution any one person can make to so great an enterprise as this. I want to associate myself with his comments:

For me, if it be God’s blessed will that in the years now coming I am to have a share in the great undertaking, which has been the occasion and the subject of [my remarks], so far I can say for certain that, whether or not I can do any thing at all in [Blessed John Newman’s] way, at least I can do nothing in any other. Neither by my habits of life, nor by vigour of age, am I fitted for the task of authority, or of rule, or of initiation. I do but aspire, if strength is given me, to be your minister in a work which must employ younger minds and stronger lives than mine. I am but fit to bear my witness, . . . to throw such light upon general questions, . . . as past reflection and experience enable me to contribute. I shall have to make appeals to your consideration, . . . of which I have had so many instances . . . ; and [we must not] be surprised, should it so happen that the Hand of Him, with whom are the springs of life and death, weighs heavy on me, and makes me unequal to anticipations in which you have been too kind, and to hopes in which I may have been too sanguine.

1 The Idea of a University xl (University of Notre Dame Press 1982).

2 Id. at 113.

3 Id. at 46.

4 Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow, The Grand Design (2010).

5 Stephen Jay Gould, The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (2002).

6 The Aims of Education (2001)

7 Nicomachean Ethics Bk. VI, ch. 8.

8 United States ex rel. Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347 U.S. 260 (1954).

9 He’s quoting St. Gregory and St. Isidore.

10 Nicomachean Ethics 1095b.

11 Nicomachean Ethics 1144a.

12 The Feeling of Things, the Contemplation of Beauty, on line at The Crossroads Initiative (August 2002).

13 Blaise Pascal, Pensées 250, 252.

14 The Feeling of Things, the Contemplation of Beauty.

15 Catechism of the Catholic Church 2030.