Good afternoon and welcome to my blog. If you are regular readers or visiting for the first time, I hope you enjoy reading the blog and viewing the pictures from this week’s activities.

On Sunday, I traveled to St. Joseph Parish in Lynn for the celebration of “el Santo Cristo Negro de Esquipulas.” Esquipulas is a town in Guatemala, and at the Benedictine abbey there is a very ancient crucifix made 500 years ago.

This image of Christ was made by a Portuguese immigrant for the community there, and it’s carved in black wood — Central America is famous for its precious woods. The crucifix is a great object of devotion and has been a great source of pilgrimages. Miracles have been attributed to the prayers of visitors who pray in front of the image.

The parish community at St. Joseph’s serves many new immigrants from different Latin American countries as well as its English-speaking community. The Guatemalan community and the Dominican communities are the two larger groups in the parish.

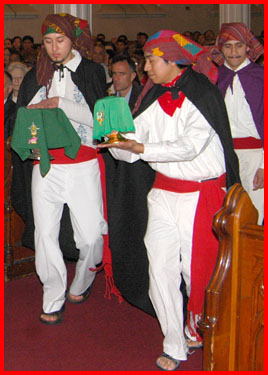

The Mass for “el Santo Cristo Negro de Esquipulas” was a beautiful celebration. They had wonderful choirs singing, and many of the Guatemalans were in their native costumes. Guatemala is the country in the hemisphere that has the largest percentage of indigenous people. Unlike many of the indigenous peoples in the Americas, the Guatemalans have preserved their languages and their customs.

The headdress is typical of the Guatemalan traditional dress.

And these women here are all in typical garb

There were also many children present.

The pastor at St. Joseph’s, Father Jim Gaudreau has a very active outreach and evangelization. He’s a man of such great dedications and has shown great pastoral care of Hispanic immigrants. He has a very creative and zealous way of reaching out to the people. He said over 500 people are taking Bible classes at the parish.

Father Jim Gaudreau

There is also a large Brazilian community in the parish and a wonderful group of sisters from Mexico, las Hermanas Misioneras Servidoras de la Palabra, who are doing good work at several parishes in the archdiocese, including St. Joseph’s. They train many people to do home visitations and focus on adult faith education, which is very important.

– – –

Also on Sunday I took part in the annual assembly for the Massachusetts Citizens for Life held in Boston’s historic Faneuil Hall. Attorney Phil Moran delivered the keynote address. He gave a fine presentation on the pro-life issue in our present circumstances. Several others spoke as well including Ambassador Ray Flynn, MCFL president Joseph Reilly, executive director Marie Sturgis and board members Father David Mullen and Mildred Jefferson also spoke.

Phil Moran

Dr. Mildred Jefferson

I addressed the crowd as well and thanked the MCFL and all those who have participated in the great work they do. Every year they have organized a rally in October that is an important way for the local community to mark pro-life month, and we’re grateful for that. We know that they’ve had struggles, but their new capital campaign is a moment for them to reaffirm their mission and it is an important way for the Catholic community to work with other churches as well as secular organizations who stand together in favor of life. I ended my comments with the peace prayer of St. Francis and a blessing.

My address to the assembly

– – –

Later on that evening, we had a vespers ceremony at St. John’s Seminary in memory of Martin Luther King, Jr. The Archdiocese of Boston Black Catholic Choir did a magnificent job. Pierre Monette presented a dramatic reading of Martin Luther King’s “I Been to the Mountaintop” speech, which was superb. Everyone was very moved. He did it in a very passionate way and very convincingly. Lorna DesRoses coordinator of Black Catholic Ministry in the Office of Cultural Diversity did an excellent job putting together a wonderful evening of prayer and song.

The Black Catholic Choir performing

The talk that I gave at the event was based on a Pastoral Letter on Racism, “Solidarity: Arduous Journey to the ‘Promised Land’” I wrote in the year 2000 while Bishop of Fall River.

I’d like to share that text with you:

Jesus’ ministry is a clear manifestation of the universal love of the Father; for beyond His ministry to the Chosen People of Israel, Jesus reaches out to the pagans, curing the centurion’s servant. The daughter of the Syro-Phoenician woman, as well as the possessed Gerasene man in the Decapolis, are also beneficiaries of the Lord’s healing power. The Apostles themselves are surprised to find the Lord talking to the Samaritan woman at the well and certainly disconcerted by His bold assertion that many would come from the east and the west and would sit down at table with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob when God’s kingdom is realized.

The irresistible logic of Christ’s teaching allows the Church to be truly Catholic, and to embrace the universalizing implications of the Gospel message. Paul, the Apostle of the Gentiles, saw the breaking down of the wall of hostility between Jew and Gentile as one of the great watersheds in the history of salvation. The Church proclaims our God who shows no partiality except, perhaps, for the margin-alized and excluded. St. James warns us about being “partial towards persons,” about discriminating against those who are poor, or different in favor of the rich and famous. St. James, in his epistle admonishes us:

“My brothers, as believers in our Lord Jesus Christ, the Lord of Glory, you must never treat people in different ways according to their outward appearances” (James 2:1). The Sacred writer goes on to condemn this discrimination: “you are guilty of creating distinctions among yourselves and of making judgments based on evil motives” (James 2:4).

The teaching of Christ is unambiguous that the whole of our religion, “the Law and the Prophets” is based on the Great Commandment of Love. No matter how outstanding our talents or contributions, “if I have not love, I am nothing” (1 Cor 13:2). If we claim that we love God but hate our neighbor, then we are “a Liar”; for “one cannot love God whom he has not seen, if he does not love his brother, whom he has seen” (1 John 4:20).

When asked for a definition of neighbor, our Lord answers with the parable of the Good Samaritan. Jesus astonished his audience by making the Samaritan, the member of a despised minority group, the hero and protagonist of the story. In one fell swoop Jesus pops the bubble of ethnic superiority and at the same time challenges us to be a neighbor to all in need and to remove the barriers in our heart that prevent us from seeing our connectedness with every human being. For when Jesus says neighbor, He is talking about a big neighborhood: first of all anyone who is in need and has a claim on our help, as well as every man, woman and child of whatever religious persuasion, social status, ethnic or linguistic background, liberal or conservative, heterosexual or homosexual, Democrat or Republican, old or young, and all of the above, in all shades, colors and sizes. There is absolutely no room for racism and discrimination in Jesus’ concept of neighbor.

We can truly love God only when we truly love our neighbor, made in His image and likeness. Apart from that love, there is no authentic religion. Because love is the essence of our religion, racism is a dangerous heresy that subverts the announcing of the Gospel.

The history of our country has been deeply marked by the sin of racism, which is a betrayal of our Christian faith as well as our democratic ideals. Despite great progress in the area of civil rights since the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., his dream of racial harmony is still a dream deferred. The “promised land” of integration where “children of former slaves and children of former slaveholders could sit down at the table of brotherhood,” so much more difficult than desegregation, is still very elusive. Church burnings and other hate crimes continue, and motorists are still stopped for “driving while black.” In the last year, 220 articles on racial violence appeared on the pages of The New York Times including the tragic high profile accounts of the torture of Abner Louima and the killing of Amadou Diallo.

It is with shame and sorrow that we recall the plight of Native Americans and Blacks, the two groups to suffer the most devastating effects of the sin of racism in our country. It is obvious that racism in all its forms and disguises is a dehumanizing force that demeans its victims and renders its perpetrators diminished in their humanity, or to use an expression of Pope Paul VI, “mutilated by their selfishness.”

The racial tensions in the U.S. find a counterpart in the ethnic and nationalistic violence abroad. In fact, of the 50 million people who have died in armed conflicts since the end of World War II, most have perished in “ethnic” conflicts — in Rwanda, Burundi, Angola, Mozambique, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, East Timor and the former Yugoslavia. The dawn of the new millennium finds the whole world struggling with a legacy of devastating racial and ethnic violence.

The challenge for believers is to build a civilization of love in a world where there is so much division. The ministry of reconciliation is a sacred duty of Christ’s Church. Diversity must be seen as something that can enrich the human family. We must move from fear and suspicion to tolerance and from tolerance to solidarity. This is not a utopian quest but a moral imperative for peace and progress on our planet. Indeed, it is probably a question of survival. There will be a civilization of love or no civilization at all.

To combat racism at its root, we must begin with a personal inventory, an examination of conscience and a profound realization of how pernicious racism is. Racial bias profoundly affects our culture. It deforms relationships within and between racial or ethnic groups. It undermines the possibility of true community. In addition, racial bigotry exacerbates unhealthy competition, destroys people’s self-confidence and initiative. This sin prevents us from being what God has called us to be.

Racism has many faces, not just a pointed hood of the white supremacists. It is evidenced in one’s tendency to stereotype people, in an extreme pride in one’s own country or race, in belittling members of other races, in condescending attitudes or behavior, and in not taking peoples of other races seriously. A racist attitude finds expression in a lack of impartiality, in the failure to recognize the negative impact of racism on the victim, by encouraging prejudice in others and laughing at racist jokes that are hurtful and demeaning.

In the Parable of Lazarus and Dives, the rich man goes to Hades, not for adultery, or murder, or robbery, but because he was incapable of seeing Lazarus suffering at his doorstep. In a similar fashion, racism makes one blind to the presence of persons of other races. They become like nameless pieces of furniture that clutter up the landscape. Racism will be banished when we overcome our blindness to the people around us; and when instead of being blind, we become color blind, indifferent to people’s complexion, but not to their dignity and their feelings.

Desegregation was the process which eliminated discriminatory laws and barriers to full participation in American life. Integration is much more difficult to achieve because it demands a change of heart. Desegregation may unlock doors, but integration is when minds and hearts are opened as well, when the welcome mat is placed at the door.

Integration is so compelling because it is about people, not laws. It is about the way we see each other and treat others, it is about whether there will be room in our hearts and homes and classrooms and clubs and churches to welcome each other naturally as neighbors and friends. Desegregation is about laws; integration is about the Golden Rule.

In the play “South Pacific,” Rodgers and Hammerstein have a song that goes: “You have to be taught to hate and fear. You have to be taught from year to year. It has to be drummed into your little ear. You have to be carefully taught.”

Racism is like a disease most often transmitted from parent to child. Its early symptom is the delusion that one’s race is somehow superior to others. In advanced stages, it leads to hatred, violence, and untold suffering. This contagion needs to be checked. The 20th century was able to entirely eliminate certain diseases like small pox and polio, but this spiritual disease of racism is still menacing our world as we begin a new millennium.

In the fight against any disease it is necessary to recognize the threat. Too often we are in denial about racism. The reality has been driven underground. Because cruder historic forms of racist sentiments and behavior are considered “politically incorrect,” and because more laws have been passed, more “concessions” made, there is a false sense of security that the problem has been dealt with. But too often the spiritual problem has not been dealt with: repentance, change of heart, forgiveness, respect are still needed. Today’s racism is more subtle but no less real. As the United States Catholic Conference Document, “Brothers and Sisters to Us,” asserts racism, “is manifest also in the indifference that replaces open hatred. The minority poor are seen as the dross of a post-industrial society — without skills, without motivation, without incentive. They are expendable. Many times, the new face of racism is the computer printout, the pink slip, the nameless statistic. Today’s racism flourishes in the triumph of private concern over public responsibility, individual success over social commitment, and personal fulfillment over authentic compassion” (B.S.T.U. 1997, p. 6).

In Catholic social teaching, the antidote for racism is Solidarity. It is a concept used by Paul VI in “Populorum Progressio” in his discussion of development. Pope John Paul II expands on this virtue in his Encyclical letter “Sollicitudo Rei Socialis”: “In the light of faith, solidarity seeks to go beyond itself, to take on the specifically Christian dimensions of total gratuity, forgiveness and reconciliation. One’s neighbor is then not only a human being with his or her own rights and a fundamental equality with everyone else, but becomes the living image of God the Father, redeemed by the blood of Jesus Christ and placed under the permanent action of the Holy Spirit. One’s neighbor must therefore be loved, even if an enemy, with the same love with which the Lord loves him or her; and for that person’s sake one must be ready for sacrifice, even the ultimate one: to lay down one’s life for the brethren” (S.R.S. #40).

Solidarity is an expression of the great commandment that calls us to form a community among people that will enable us to overcome “structures of sin and oppression” that dog humanity. Above the human and natural bonds already so strong, faith leads us to see “a new model of the unity of the human race.” The Holy Father insists that Solidarity is not sentimentality or a vague compassion or empathy for the suffering of so many, but rather it is a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good, that is to say the good of all and of each individual, “because we are all really responsible for all” (SRS #38).

We must embrace the concept of solidarity as a solution to racism, as well as to the greed and the competition that has fractionalized our country and our planet. Solidarity is the virtue we need to instill in the new generation so that racism might become a sad anachronism in our lifetime. Just as racism is contagious, so too solidarity can inspire our young people when they see the witness of men and women committed to social justice and the good of the entire community.

As we campaign against cigarettes and drugs, we must also launch a campaign of zero tolerance for the intolerance of racism. Parents and teachers need to be the protagonists of this effort. Each of us ought to begin with our own personal conversion and testimony. We also need to create opportunities and space for friendship with people who are of different races and ethnic backgrounds. As a community we should celebrate the gifts and the traditions of all “our neighbors” and work together to build a better community where people care about each other.

Racism thrives on fear, but love casts out fear. Solidarity transforms relationships and connects us with each other. Fear and suspicion are changed into a sense of partnership in a community that truly recognizes the value of each and every person as irreplaceable and as precious in the eyes of God.

The virtue of solidarity is not only an antidote to our racial tensions in our own country, but points the way to a program of development and world peace based on a “new model of the unity of the human race.” In his message for World Peace Day, Pope John Paul II states: “… we can set forth one certain principle: there will be peace only to the extent that humanity as a whole rediscovers its fundamental call to be one family, a family in which the dignity and rights of individuals, whatever their status, race or religion, are accepted as prior and superior to any kind of difference or distinction” (World Day of Peace #5).

Given the U.S. economic, cultural and military power, the Holy Father’s dream of humanity becoming “a single family built on the values of justice, equity and solidarity” is in some ways contingent on the ability of Americans of good will being able to bring about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of the “Promised Land” of racial integration in our corner of the globe. Our quest is to become what God has called us to be.

– – –

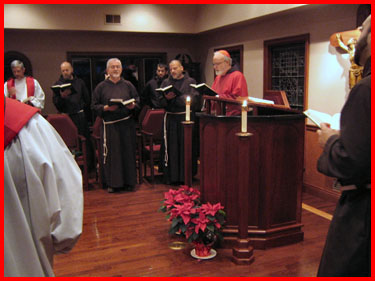

The archdiocesan offices were closed on Martin Luther King Day, and I took advantage of that to visit our novitiate in Pittsburgh. I had not been there for a few years and the friars have been encouraging me to come. It was an opportunity to be with the novices and speak with them. The evening that I was there, they had a Mass for a third order group. The lay people came in, had a Mass and visited with the novices. It was a very nice event.

Here’s a picture with all the friars in the chapel:

There are about a dozen novices right now and about 30 members of the community.

There are two beautiful windows in the novitiate, depicting St. Francis — one of him building the Church and the other of when he gives his clothes back to his father.

patroness of Bavaria, is also in the novitiate

St. Conrad was a member of the German province of the Capuchins, that I joined in Pennsylvania. The Capuchins established the community of St. Augustine in Pennsylvania to minister to the large German immigrant population. St. Conrad used to serve Mass for the first rector of the seminary where I studied. St. Conrad was a porter at a very famous Marian shrine in Germany called Altoetting. He lived between 1818 and 1894.

Some photos of the Shrine of Altoetting

The interior of the Church of St. Conrad in Altoetting

with those who rang the doorbell of the Capuchin monastery

In fact, the last time the Holy Father was in Germany, he visited his grave. St. Conrad is the only German canonized from the time of the Reformation until modern times when John Paul II canonized some Germans. He was, as I said, a porter, lay brother at this very important Marian shrine.

The novitiate was a wonderful time in my life, and I was happy to be with the novices who were so filled with joy and enthusiasm for their vocations. It took me back to my novitiate, which was in 1964. In those days we went to college for two years at St. Fidelis in Pennsylvania and then we went to novitiate in Annapolis Maryland. After the novitiate, we went back to Pennsylvania to study Philosophy . Then I went to Washington D.C. to study theology.

The statue of St. Conrad, the same crucifix and a lot of other religious symbols which are currently in Pennsylvania used to be in Annapolis.

The crucifix

Also visiting the novitiate was one of the priests who I was in the seminary with, Father Bill Fay. He was home visiting his mother. He is now teaching at our national seminary in Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea. Previously he taught at Oxford University. He’s a very accomplished theologian, and he has also taught at our seminaries in Africa.

Celebrating Mass with the community

Some photos with the novices

– – –

This weekend I will be heading to Washington D.C. for the March for Life on Monday. I’m very happy that there will be a number of buses going down from the Archdiocese of Boston. Many parishes, Catholic high schools and the Vocations Office will be sending buses. The march is always a wonderful event. It’s an opportunity for young people to experience the universal Church and to be a part of this very important campaign on behalf of the dignity of human life. We participate in this campaign as believers, and it’s part of our commitment to discipleship.

I urge all of you to pray for an increased respect for life in our culture and the whole world. Even if you are not able to travel to Washington, you can send your prayers with all those who are able to go.

For the photo of week, I’d like to share this photo of the sun setting behind a statue of Our Blessed Mother in Altoetting.

Yours in Christ,

Cardinal Seán